"Seasickness appeared:” The first SSND voyage to North America

“Yesterday, Friday, July 30, at five in the evening, we set foot on solid ground for the first time in America – in New York. I am forced to keep silence about our gratitude to God because I, the most miserable of all, would never come to an end.” Mother Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger, later known as Blessed Theresa, wrote these words at the end of the long and arduous trip from Munich to New York. She left Bavaria with the intention of establishing a motherhouse in a small settlement in St. Mary’s, Pennsylvania, but first she needed to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Mother Caroline walks with a novice sister.

Much has been written about Mother Theresa’s first and only trip to the United States, but little has been written about the actual journey to North America. Mother Theresa wrote about the trip in letters home, providing a lot of detail about how difficult the ocean crossing was for her. The youngest members of the travelling party, Sister Caroline Friess and Novice Emmanuela Breitenbach, kept a travel diary, which provides a very detailed account of the trip. Sister Caroline affectionately became known as Mother Caroline later in life.

The trip was long and difficult and things did not get any easier once they arrived in the United States. However, Mother Theresa’s determination to make the crossing allowed her to plant the seeds for the School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) in North America.

“School Sisters’ call to America…”

In 1846, Mother Theresa received a request to establish a motherhouse in a small German Catholic settlement in Pennsylvania. She had received other such requests in the past, but the time was never right to seriously consider such a move. However, this came at a moment when the congregation’s growth was stifled because of a decree issued by the Bavarian Royal Government that subjected the profession of vows for women religious to the decision of a state commissioner.

Mother Theresa had 40 novices who were unable to profess their temporary vows and she worried that, on the advice of their parents, young women would choose to delay entering religious life. Although she continued to admit women to the candidature, she was concerned about what to do with them, “In the meantime there they remain in the motherhouse without resources and without purpose.” She wrote that the situation with the government, “Will determine the order’s further growth in the number of convent personnel as well as of newly established institutes…Under such circumstances, our hands are tied.”

It was during this period of uncertainty that Baron Gottlieb Henry von Schröter, a representative of the settlement in Pennsylvania, travelled to Munich and asked King Louis I and the archbishop of Munich, to recommend a congregation of women religious to teach at the settlement’s school. The king and the archbishop encouraged Mother Theresa to accept the request and the king offered to finance the trip and the erection of the motherhouse.

Mother Theresa agreed. In a letter to the archbishop, she wrote, “The respectfully undersigned considers the School Sisters’ call to America as a sign of Divine Providence mercifully directing us to a new field of activity. We could confidently send our novices there because they would be allowed to make their profession without interference, to live as religious, and to follow God and their religious vocation.”

“With painful tears…”

Mother Theresa made the decision to accompany the missionary sisters to North America, but she planned to return to Bavaria once everything was settled. The missionaries, however, were making a one-way trip – those who volunteered did so with the understanding that they would remain in the United States for the rest of their lives. In the end, Mother Theresa chose four professed sisters, Magdalena Steiner, Mary Barbara Weinzierl, Seraphine von Pronath and Caroline Friess, and a novice named Emmanuela Breitenbach, to make the trip. Mother Theresa did intend for Novice Emmanuela to accompany her when she returned to Bavaria, but unfortunately, the young novice died from dysentery shortly after the group arrived in the United States.

On June 18, 1847, “With painful tears and fervent good wishes for blessing,” Mother Theresa, the four sisters and the novice set out from the Munich motherhouse. The group travelled by carriage, stopping at the convents in Pfaffenhofen, Bavaria, and Ingolstadt, Bavaria, before reaching the Benedictine convent at Eichstätt, Bavaria, where they spent the night.

At 3 a.m., the group dressed and went to the chapel to receive Holy Communion. The Benedictine superior presented the sisters with three small spoons of St. Walburga oil and a relic of the saint to kiss. “We were all very much affected and could not hold back our tears, because the double sacrifice which the Lord wanted from us today was not easy. We were to take off the religious habit and leave our Reverend Father [Siegert]. Both weighed heavily on our souls.”

After breakfast, the sisters and the novice changed into secular clothes, which they would wear for the duration of the trip. The group left the convent and Sister Caroline’s uncle, who was the dean in Eichstätt, Bavaria, and Father Matthias Siegert, the congregation’s confessor, traveled a short distance with the group. When they made their goodbyes, the two men, “Shook hands with us and blessed us, but were themselves hardly able to speak. They watched as the carriage went down a long street until a turn hid them from us and us from them.”

The Trip to Bremen

From Eichstätt, Bavaria, the travelling party took a series of trains, carriages and wagons to reach the port city of Bremen, Bavaria. Novice Emmanuela and Sister Caroline kept a travel journal in which, they recorded all they saw – the construction of the houses, what the locals wore, what types of crops were grown and more. They also wrote about some of the mishaps they encountered, including the rude “herb woman” in Bamberg, Bavaria, who, “Began to grumble rather loudly, because by mistake my umbrella came somewhat close to her.” At the guesthouse in Hannover, the room was so small, “six persons could hardly move. We wanted to stay together, however, and when we wanted to rest for the night, we had to look for a broom so that we could sweep the floor first before lying down.”

It is important to remember that in 1847 Germany was not a country, but rather a loose confederation of independent states that shared little more than a common language. The customs, laws, religion, dress, food, etc. varied across the different states, so, as the sisters travelled north, they experienced some culture shock. In northern Bovaria, Novice Emmanuela wrote that while German was spoken there, “We were hardly understood anymore.” In Reichenbach, their ignorance of the local currency caused them to pay several dollars too much for their railroad tickets, however, the railroad inspector helped them secure a refund. They were also shocked by the cost of things, including the price of a liter of beer, which cost 15 kreuzers!

On June 24, they reached the port city of Bremen, Bavaria. At the inn there, they met Baron von Schröter, who planned to accompany the group to New York. It was reported that he, “Could not refrain from laughing heartily at us and teasing us with the comment that the religious habits fit us much better [than their secular dresses].”

They rose at 4 a.m. the next morning, went to confession, and received Holy Communion. They knelt before the Blessed Sacrament and prayed for a safe journey. At 10 a.m., “Surrounded by a large group of spectators and with hearts that were both anxious and deeply moved, [they] climbed down a few steps into the smoking steamboat,” that would take them down the Weser River to the port of Bremerhaven, Bavaria. As they steamed up the Weser, the group was delighted by, “large fish, called porpoises, which usually appear in the sea only during a storm, swimming right past the ship and doing amusing jumps over the water.”

After a journey of several hours they arrived at the ship that would take them to New York—the Washington.

“This magnificent vehicle…”

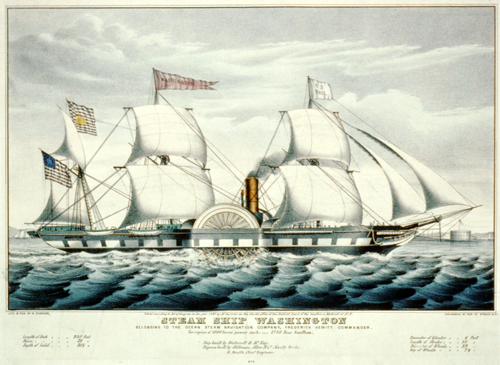

Steamship Washington Lithograph. Provided by Library of Congress.

Novice Emmanuela wrote about the experience of seeing the ship for the first time,

“… The renowned Washington anchored before our eyes. At the sight of it, varied feelings took hold of us. Coming closer to it, we viewed with big eyes the enormous ship and could not gaze enough in admiration of this little Wonder of the World. The thought that this magnificent vessel was to bring us across the vast ocean and to a faraway continent, and who knows whether I shall leave it alive or dead, powerfully urged us to turn eyes and hearts in fervent prayer to God who, enthroned on high above us, guides with infinite fatherly love the destinies of the children of God and who alone is Lord and Master of Life and Death!”

The Washington was about to embark on its maiden voyage across the Atlantic. The ship, named for George Washington, was 255 feet long and 39 feet wide. It was “beautifully equipped,” with a drawing room, cold storage rooms to house food and a string of boats that had, “No other purpose than that the people could save themselves on them if the ship had an accident.” The cabins where the group stayed were outfitted with two berths, one above the other. Each bed had a small mattress, a little pillow and a white woolen blanket. The floors were carpeted and the window openings were round and very small. Most importantly, there were tin vomit-basins fastened to each of the beds.

The following morning, the group boarded the little steamboat and again, “Amid the tears of friends who until now were accompanying travelers, as well as the firing of a few cannon shots, we boarded the Washington, this time to stay. Even this far many people still accompanied the departing ones and left them only at the farewell call customary on the ship; Hip, hip, hurrah! – whereby the men wave their hats, the ladies their handkerchiefs…Then, amid the singing of the sailors, about 30 of whom were turning the iron chain, the enormous anchor was pulled up…Then we went through the mouth of the Weser and out into the North Sea.”

The ship took three days to cross the North Sea and the English Channel. The first two days passed without incident, but on the third day several of the sisters, including Mother Theresa, became ill. Mother Theresa recovered and that evening she, accompanied by Sister Seraphine and Novice Emmanuela, sat on the deck and, “Enjoyed the beautiful view for a while.”

England

On June 28, the ship docked at Southampton, England, and there it remained for several weeks. Prior to landing, the ship’s captain informed the passengers that the ship would have to dock for a few days to undergo several repairs. The sisters remained on the ship for a few days and then moved to a hotel in Southampton.

Meanwhile, Baron von Schröter and Father Stauber, a German priest travelling on the Washington, found the nearest Catholic Church and asked permission for Father Stauber to say Mass there. The priest told them they would need permission from the bishop in London, so the Baron, Mother Theresa and Novice Emmanuela took a train to London. Mother Theresa met with the bishop, who gave permission for Father Stauber to celebrate Mass at the church in Southampton, England. The three also did a little sightseeing—they visited St. Paul’s Cathedral, drove past the new parliament building and visited the large bridge that crossed the Thames.

The four sisters who remained in Southampton, however, were not having as much fun. In the morning, they went to the Catholic Church to attend Mass, but since the church had no bell, they arrived too early. They entered the empty church, sat down near the front, and were, “Highly delighted with their good place. Soon, however, the old sexton came along and informed them with a rough voice to either leave these places or pay 11 pence per person, which everyone who was coming in promptly did. They had no money with them and willingly withdrew to the back of the church.” A schoolteacher took pity on them and convinced the priest to let the sisters sit at the front of the church for the duration of their stay in Southampton.

The sisters visited various sites around Southampton, England, while they waited for word that the Washington was ready to sail. Finally, on July 9, they saw the, “Large, colorful flag at the highest point of the Clairenton Hotel that told us and all of Southampton, that tomorrow, on July 10, the great Washington would set sail for America.”

On the morning of July 10, they boarded the ship and left England. They went to bed that night fully expecting to wake up in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean; instead, they awoke to find they were within sight of land. “But what a horror now for all when soon we heard that since three o’clock in the morning the ship was moving backwards again!” The coal contained too much calcium, which put the ship at risk of fire, so the captain made the decision to return to Southampton, England.

On July 15, “The Washington’s third trip was scheduled, which actually did take place.” The following morning the ship was still in the English Channel when those on board witnessed the sinking of a large ship. The sisters watched as the, “Vessel sank ever deeper and deeper into the water, and soon only the masts with the sails could be seen.” Thankfully, the people on the ship were able to use the lifeboats to make it to the shore. However, the sight must have been very unsettling for the passengers who were about to enter the open waters of the ocean. “For us it was indeed an admonition from above, which urged us to zealous prayer before entering the wide ocean. But soon we were in a condition that made it almost impossible for us to pray.”

“Seasickness appeared”

After landing in New York, Mother Theresa wrote about the trip across the ocean, “Of the beautiful and wonderful natural phenomena of the ocean, the magnificent and picturesque coastal area of America, the grand seaport of New York that far surpasses England’s port, I must be silent and let our Sisters Caroline and Emmanuel tell you, because God let me see nothing of them.”

Mother Theresa later reported that the English way of life, including the air, drinking water and food, did not agree with her. She also had to board the ship three times and endure seasickness and nausea each time so that, “By the time we reached the high seas on July 15, I was in a very weakened condition.”

She was not the only one who struggled to adjust to the constant movement of the ship. Novice Emmanuela reported that, once the ship hit the high seas, the larger waves caused the ship to rock more. “Seasickness appeared,” and the healthy passengers on deck left one after the other as each eventually succumbed to the illness. She wrote, “However, soon here, soon there, neither men nor women could stay on their feet any longer. From all sides one heard people calling to one another in German, English, French: ‘Krank, sic, malad?’ And by mealtime at one o’clock all the women and half the men had disappeared.”

Within a day of leaving England, everyone in Mother Theresa’s travelling party came down with seasickness. Sister Caroline and Novice Emmanuela were able to stay on deck longer than the others, but eventually they too became ill. When Sister Caroline became sick, the Baron attempted to walk her to the cabin, but he did not notice an open trapdoor and he fell into a deep part of the ship. Fortunately, he was uninjured.

Novice Emmanuela described the gruesome scene: “One after another had to vomit, often two or three at the same time. They had scarcely risen a little from the floor or from the bed when they either had to vomit again or, due to the swaying of the ship, dropped back down again.”

Novice Emmanuela reported that she was the least sick of the party, and she vomited 12 times and was so weak that she was unable to climb into bed and laid on the floor for a time. She wrote, “Besides the illness mentioned above, seasickness also causes constant nausea and an overpowering disgust for all food so that one feels such fatigue in the limbs that it is impossible to stand or walk. Thus it continued for several days, and we could not do or enjoy anything.”

Most of the group recovered after a few days, but Mother Theresa suffered greatly for the duration of the voyage. She had a high fever, “Burning thirst and a vehement disgust for all food and drink.” She was so nauseous that she could not hold down a drop of water and the vomiting was so intense that she coughed up blood three times. The sisters attending her used the homeopathic medicines they had brought with them, but nothing helped.

Mother Theresa later wrote that the daily hustle and bustle of life on the ship tormented her from morning until night. To make her condition more bearable, she would imagine that God was allowing her to experience something of purgatory. “Nevertheless, I was still hopeful because I could roughly calculate when my sufferings would end, but the poor souls do not know the time of their release.”

While Mother Theresa suffered below deck, the young sisters and a novice, who had recovered their health, enjoyed the onboard entertainment. In the evenings, “Strolling on the deck began with music, dancing, fun and games, and masquerade, often through half of the night or at least until 12 o’clock, when all had to retire at the given signal.” The sisters enjoyed standing on deck and watching the schools of fish. At one point, they spotted six whales playing in the water.

On day 15 of their journey, they spotted the American shore. “The joyful cry, ‘Land!’ awakened new life in all the passengers. Before they even saw land, all who were still seasick seemed to sense its nearness and could now get up and walk and see.”

The Washington pulled into the New York Harbor. “The flags were raised and, all of a sudden, the Washington stood still—it had reached the destination of its perilous voyage. The heavy anchor was dropped, and the sailors’ beautifully harmonious song resounded in alternate choirs, this time in triumphant joy over their safe arrival.”

Mother Theresa exited the ship in a much-weakened state. She wrote that she looked 10 years older and felt like a helpless child. She was suffering from terrible headaches, her eyes were weak and her teeth were hollow, “In short, the entire, miserable machine is no longer of much use.” Yet, despite all the hardships, they had made it.

The sisters stepped off the Washington and onto their new mission field.

You can learn more about the history of SSND from the archivist, Michele.