By Tim Cary, Archivist

On September 1, 1948, in Strasburg and Mantador, North Dakota, an interesting side note in the history of the School Sisters of Notre Dame (SSND) began. A new school year was about to begin, and the teachers at the schools in those towns (Sisters Celine Koktan, Lucida Kunz, Thomas Caven, Isabel Kathrein, Josepha Forster, Kathleen Rother, Richard Anthony Schutte, Thomas Aquinas Schmitt, Seraphica Guter, and Louis Pihaly) were about to have two unusual things in common. One, this would be their first day teaching in a public school. Two, it would be the first time that any of them would appear in their classrooms in civilian “garb,” and not in their habits. In June 1948, the citizens of North Dakota voted into law an “anti-garb proposal” which stated that “No teacher in any public school in this state shall wear…any dress or garb indicating the fact that such teacher is a member of or an adherent of any religious order, sect, or denomination.” How was such a law passed, and how did it affect the SSND who had to obey it?

Sister Richard Anthony Schutte in the Strasburg school library with three fresh-faced students in 1948.

There were a couple of reasons why Catholic sisters were even teaching in public schools in North Dakota. First, following World War II there was an acute shortage of qualified teachers. Some towns responded to the shortage by hiring well-qualified sisters to teach at all levels. Hiring sisters to teach in publics schools saved taxpayers money because they were paid less than their secular counterparts. Second, most public school districts in the state lacked sufficient funds to keep school buildings in good repair. To address that issue, some communities rented school space from Catholic parishes with existing schools. (This is what occurred in Strasburg.) This practice effectively turned those parishes into de facto public schools. This also saved taxpayers money by eliminating the need for them to pay for buildings and taking care of new schools.

By 1948, sisters had been teaching in public schools in the United States for many years. In North Dakota women religious teachers were first hired in 1918. The first lawsuit in the state against the practice occurred in 1936. In that case, taxpayers sought to prevent teachers (sisters) from wearing “religious garb” in the classroom and to stop paying sisters with school district (i.e., public) funds. The North Dakota Supreme Court ruled in favor of the sisters. The court said the school in question was not sectarian because the sisters who taught there were employed by public officials. Regarding the clothing worn by public school teachers, the court found that “the laws of the state do not prescribe the fashion of dress of the teachers in our schools.” In other words, religious garb in the classroom violated no law.

In 1947, the year before the anti-garb legislation took effect, there were 74 sisters (from six congregations) teaching in 11 counties in North Dakota. Their numbers constituted a very small percentage of the total number of teachers in the state. Still, sisters teaching in public schools concerned many citizens. Proponents of the anti-garb position believed that sisters wearing habits in public classrooms blurred the constitutional line separating church and state. Allowing the practice to continue, in their opinions, might influence children toward Catholicism because their clothing was an ongoing reminder of the sisters’ religion. Unfortunately, many of these people expressed their displeasure with the practice through attacks on Catholics and Catholic schools.

In January 1948, anti-garb forces formed the Committee for the Separation of Church and State (CSCS). The group consisted almost entirely of Protestant ministers plus a few others. Ostensibly the committee’s goal was to prevent the sisters from wearing their habits in the classroom. It is likely, however, that the committee’s ultimate desire was to get the sisters out of public schools entirely. They believed that if the sisters were forbidden from wearing their “garb,” they would choose not to teach in public schools at all. To achieve this goal, the CSCS drafted an “initiated measure” that, if passed, would prohibit the wearing of religious garb in public schools. Ten thousand signatures were needed on a petition that would put the prospective statute on the ballot for an election coming up in June 1948. The focus was on sisters’ clothing and not the sisters themselves. It was clear that their right to teach in public schools was not in question. The committee quickly got the requisite number of signatures on their petition to guarantee its appearance on the June ballot. When it was clear that the measure would appear in the June election, the Committee for the Defense of Civil Rights (CDCR) was formed to work against its passage.

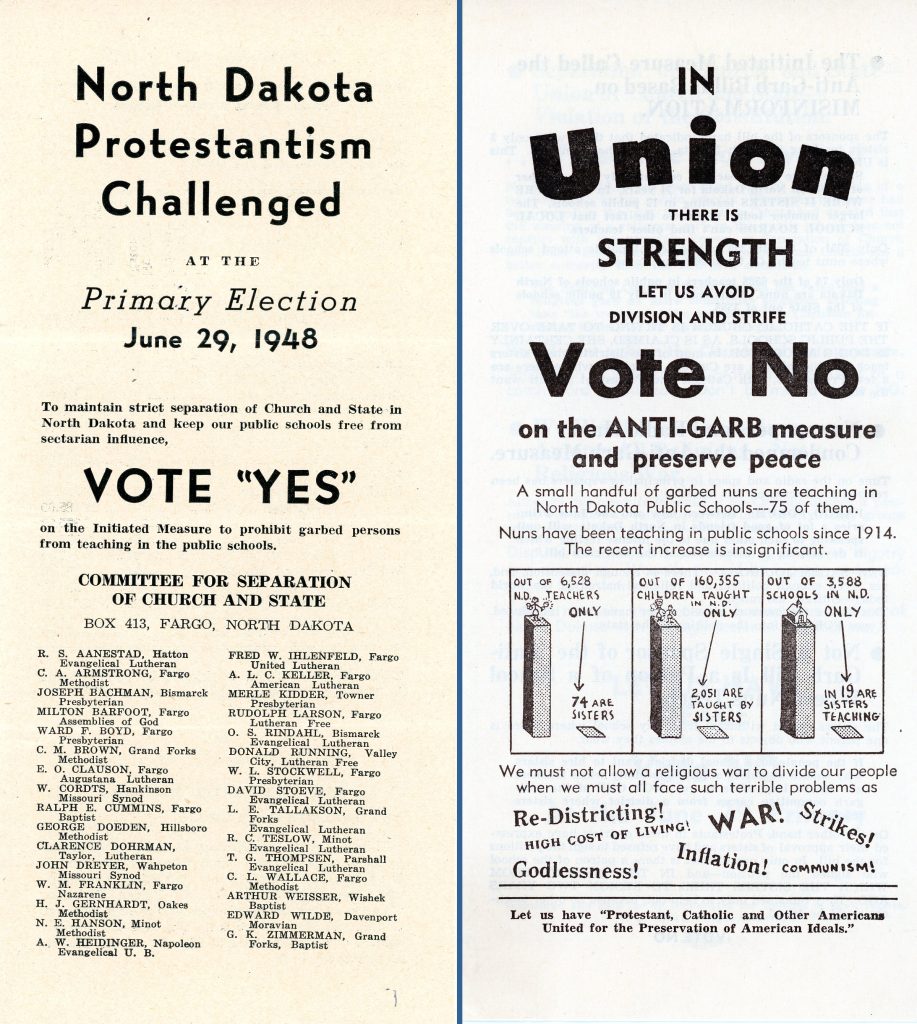

(left) The Committee for Separation of Church and State wrote the anti-garb proposal. Much of their campaign literature, like this pamphlet, used thinly-veiled anti-Catholic language to gain support for its passage. (right) This pamphlet, published by the Committee for Defense of Civil Rights, warned of “religious war” and urged voters to reject the proposal for a variety of reasons.

The CSCS and CDCR, which opposed the initiative, worked zealously for their causes. The committees’ efforts played out largely through leaflets, pamphlets and meetings. Radio stations and newspapers tended to shy away from heavily covering such a controversial issue. Supporters of the initiative used thinly veiled accusations against Catholics to convince voters to support the measure. One “pro” flier urged citizens to vote yes on the ballot because North Dakota Protestantism was being “challenged.” Those who opposed the measure stressed the importance of voting against it to “avoid division and strife,” and because there were so many other problems that required attention. Issues such as Godlessness, strikes, inflation, and of course, Communism. On June 29, 1948, the election took place and the anti-garb measure passed by a substantial margin. Sisters who taught in public schools would not be allowed to wear religious clothing in the classroom. The law would take effect on September 1, 1948.

In May, anticipating that the initiative might become law, Bismarck Bishop Vincent Ryan contacted the Vatican for advice. The Sacred Congregation of Religious advised the bishop to permit sisters to “wear modest lay garb, if necessity demands it… .” Ryan and other bishops in the region quickly communicated with all six congregations affected by the law to strategize and to ask the sisters to comply with the new law. For SSNDs, Bismarck Bishop Ryan, Milwaukee Archbishop Moses Kiley and Fargo Auxiliary Bishop Leo Binz visited or corresponded with the congregation’s Commissary General, Mother M. Fidelis in Milwaukee, and with Mother M. Annunciata, the Provincial of the Mankato, Minnesota, Province. Each man had the same message. They wanted the sisters to comply with the law. If they followed the law, Archbishop Kiley saw the sisters’ actions as a blow to “the enemies of religion.” Bishop Binz stressed the importance of presenting a united Catholic response to the situation.

Mother Fidelis and Mother Annunciata agreed with the bishops that compliance with the law was the correct response. In July, the North Dakota bishops announced that the sisters teaching in public schools would continue in their positions, and they would wear secular clothes. They had two months to figure out how to comply with the law.

This photograph, taken in 1948, shows the sisters who taught at Strasburg posing on convent steps in their WAC clothes. (Front row: Sisters Richard Anthony, Thomas Aquinas, Isabel and Kathleen; back row: Sisters Thomas, Lucida, Celine and Josepha.

SSND taught at public schools in two towns in North Dakota – Mantador and Strasburg. Mother Annunciata’s first decision was to replace the existing teachers with new ones to make the transition to the new situation easier. What would the new teachers wear? Since they did not own secular clothing, the initial thought was to use uniforms from the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). They were inexpensive, available and easy to alter. These clothes were worn for a short time, but that solution did not work well. The problem with the uniforms was that they were too much alike. The sisters wearing them were still easy to identify. Soon enough “modest lay garb” would suffice for the sisters. One sister referred to their style as “a dull suit.” When not at school, the Vatican decreed that religious garb would be worn. In the winter, the sisters were provided with a “dark brown coat with a monk’s hood attached. To meet this extra expense, school boards have raised the sisters’ salaries.”

Generally, the sisters took the new law in stride. Speaking in 1976, Sister Richard Anthony Schutte remarked, “…You could never imagine with what fears and trepidation we approached the opening of the new school year… . The first time that we made our appearance in secular clothes, it was almost a traumatic experience.” A naval officer visiting the school, upon realizing that Sister Richard was a nun in secular garb, exclaimed, “Oh, gee, if I’d only known [that you were a nun] I would’ve brought my friend along to see this!” But mostly she remembered being able to forget about the kind of clothes they were wearing because the sisters were accepted and supported by the townspeople.

Sister Celine Koktan and four Strasburg students. Notice that sister is not wearing WAC-issue clothing.

Sister Louis Pihaly (Mantador) remembered the discomfort of the “marine suit,” having to cut her hair short, and of getting her first hair perm. In Sister Lucida Kunz’s view, complying with the law was a trial, but it made the sisters into a close-knit community. Commenting on the need to change clothes as soon as they returned to the convent, Sister Celine Koktan remarked, “One does not fully realize what the religious habit means until it is taken away.” She believed that students and their parents, Catholic and Protestant, thought the law was “ridiculous.” Sister Josepha Forster summed it up well. “We taught in secular garb for 12 years. After the first few years of excitement, no one seemed to care anymore about our dress, so we started to wear our habits again.” That statement may represent the unofficial end to the “garb” issue.

Officially the practice ended in 1957 in Mantador and in 1959-60 in Strasburg. The sisters left the public school in Mantador in 1957 because it was “too far distant from any of our other North Dakota missions.” In Strasburg, the school remained public until 1959-60. Commissary General Mother Hilaria gave the pastor of the Ss. Peter and Paul parish an ultimatum: the school had to become parochial if the sisters were to remain as teachers. He complied. In 1961 the parish supported an elementary school and high school. SSND no longer wore secular clothing there, and no more sisters taught in North Dakota public schools. So ended this interesting chapter in the history of the congregation.

Source: Linda Grathwohl, The North Dakota Anti-Garb Law: Constitutional Conflict and Religious Strife, Great Plains Quarterly, 13 (Summer 1993): 187-202. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1765&context=greatplainsquarterly

This article is part of the School Sisters of Notre Dame North American Archives’ 175th anniversary celebration of SSND arriving in North America. Since July 2022, the staff at the North American Archives has celebrated this milestone each month by highlighting a particular sister, event or mission that has a unique place in the congregation’s history in the United States and Canada. Read all of the 175th anniversary stories here.